- Published on

Exploring hyperspheres and their volumes

- Authors

- Name

- Jakub Cabała

Introduction

Circles and spheres are familiar geometric shapes, and the equations governing their areas and volumes are equally well-known. The area of a circle is , and the volume of a sphere is . We were taught these formulas through years of education. But what happens when we extend these concepts to higher dimensions?

Do the elegant equations for the area of a circle and the volume of a sphere generalize to higher dimensions? What does it mean to consider a sphere in four, five, or even more dimensions? And if these equations do generalize, how can we verify their accuracy?

In this blog post, we will try to answer the questions above. We will derive the formula for the volume of a hypersphere and explore its implications. Furthermore, we will use the Monte Carlo method to verify our derived equation, combining mathematical rigor and computational experimentation.

For the most part, only basic mathematical knowledge is required to understand the concepts discussed; however, the section on the Volume of a hypersphere is a bit more involved and requires knowledge of concepts from multivariable calculus.

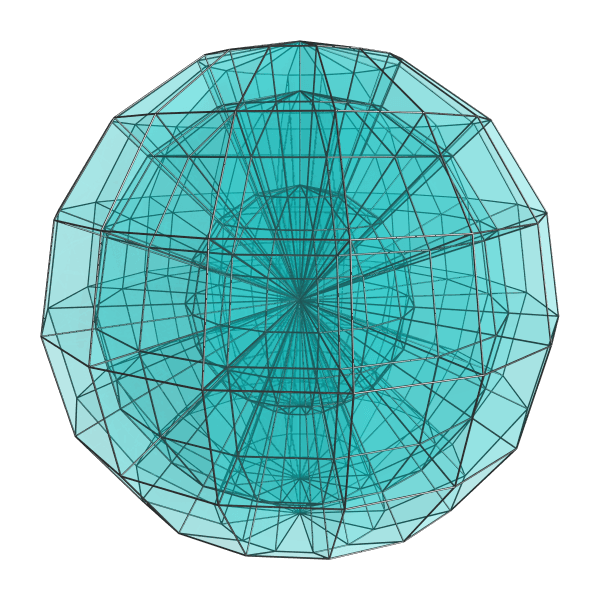

What is a Hypersphere?

A hypersphere is the generalization of a sphere to more than three dimensions. While we live in a 3D world, mathematics allows us to explore shapes and concepts in higher dimensions.

So what do we mean by a sphere in dimensions? To understand that, let's revisit "spheres" in familiar dimensions.

So following this logic, an -dimensional sphere is just a set of points equidistant from the center.

But how do we calculate the distance in dimensions? This notion generalizes nicely from lower dimensions. Each -dimensional point is represented by coordinates. For example, , are 2D points, and is a 3D point. Let represent the distance between two points. Then we have:

- In 1D, and both have 1 coordinate and

- In 2D, and are points with 2 coordinates each and

- In 3D, and are points with 3 coordinates each and

In general, in dimensions, and are points with coordinates each, and , and the distance between them is given by

Now by putting everything together, we have that a hypersphere in dimensions (an -sphere) can be described using the equation: where is a point on the hypersphere, is the center of the hypersphere, and is its radius. This equation states that the distance between any point on the hypersphere and the center equals the radius .

Volume of a Hypersphere

To derive the volume of a hypersphere, we begin by understanding the integral representation of the volume in different dimensions. In lower dimensions, we have intuitive notions of length, area, and volume. For example, the length of a line segment, the area of a circle, and the volume of a sphere are all concepts we can easily visualize. However, as we move to higher dimensions, our intuition fades, and we must rely on more abstract mathematical tools to make sense of these concepts. To make things easier let's consider spheres centered at the origin denoted by .

In dimensions, we generalize the notion of volume using integrals. Consider a hypersphere of radius in dimensions. The volume can be represented as an integral over all coordinates within the hypersphere: where which is a hypersphere and it's inside called an n-ball.

You can check yourself that solving this integral yields familiar equations in 1 and 2 dimensions: and .

Now we can derive a recursive relation between volumes in higher dimensions and volumes in lower ones. More specifically, we will prove that for all we have

.

First, we will prove a useful fact. Namely that

where is a volume of a unit ball in dimensions (ball with radius ). The proof goes like this:

Now we use a change of varialbes and calculate the Jacobian . We now get that:

Now we are ready to prove . By it is enough to show that . Here is the proof:

by

Now we are going to change to polar coordinates and get

where

To sum up, we proved that volumes of hyperspheres follow a nice recursive formula which allows us to calculate the volumes in higher dimensions easily.

Using our formula we get that:

- as expected

- . Dimension 5 is quite special as the 5-dimensional unit ball has the biggest volume.

Is there any way we can "convince ourselves" that the above result is true?

Monte Carlo Verification

We can employ the Monte Carlo method to verify the volumes of hyperspheres calculated using our theoretical formula. This method involves generating random points within a hypercube that circumscribes the hypersphere and determining the proportion of these points that lie within the hypersphere. By leveraging the law of large numbers, we can approximate the volume of the hypersphere with high accuracy.

Monte Carlo Method Explained

The Monte Carlo method is a computational algorithm that relies on repeated random sampling to obtain numerical results. It is particularly useful for estimating complex integrals and in this case, the volume of high-dimensional shapes. Here’s how we can apply it to our problem:

- Generate Random Points: Generate a large number of random points uniformly distributed within the hypercube . This hypercube contains the unit hypersphere we are interested in.

- Determine Points Inside the Hypersphere: Calculate the distance of each point from the origin using the Euclidean norm (the function we derived before). Points whose distance from the origin is less than or equal to 1 are inside the unit hypersphere.

- Estimate Volume: The ratio of points inside the hypersphere to the total number of points, multiplied by the volume of the hypercube, gives an estimate of the hypersphere’s volume. The volume of an n-dimensional hypercube is because each dimension contributes a length of 2 (from to ) and the total volume is the product of these lengths (I think it intuitively makes sense given the equations for an area of a square and a volume of a cube).

Python Implementation

Below is the Python code implementing the Monte Carlo method to estimate the volume of unit hyperspheres in different dimensions. It also includes the theoretical volume calculation based on our recursive formula.

import numpy as np

def monte_carlo_unit_sphere_volume(dim, num_points=1000000):

# Generate random points in the hypercube [-1, 1]^dim

points = np.random.uniform(low=-1.0, high=1.0, size=(num_points, dim))

# Count how many points are inside the unit sphere

distances = np.linalg.norm(points, axis=1)

inside_sphere = np.sum(distances <= 1.0)

# The volume of the hypercube [-1, 1]^dim is 2^dim

hypercube_volume = 2 ** dim

# The ratio of points inside the sphere to total points, multiplied by the hypercube volume

sphere_volume_estimate = (inside_sphere / num_points) * hypercube_volume

return sphere_volume_estimate

def theoretical_sphere_volume(dim, radius):

if (dim == 0): return 1.0

if (dim == 1): return 2.0 * radius

return 2 * np.pi * radius * theoretical_sphere_volume(dim - 2, radius) / dim

# Example usage:

for dim in range(1, 10):

estimated_volume = monte_carlo_unit_sphere_volume(dim)

theoretical_volume = theoretical_sphere_volume(dim, 1)

print(f"(Dimension, estimated volume, theoretical volume): {dim}, {estimated_volume}, {theoretical_volume}")

Conclusion

Running this code for dimensions 1 through 9, we can compare the Monte Carlo estimated volumes with the theoretical volumes from our recursive formula. The close match between these results validates our mathematical derivations and demonstrates the effectiveness of computational methods in exploring higher-dimensional geometry. This blend of theory and computation enhances our understanding of higher-dimensional concepts and their interconnectedness.

If you are interested in this topic I recommend going through this article by Jake Gipple.